Primer pulmoner non-Hodgkin lenfoma: Literat?r de?erlendirmesiyle birlikte 10 olgu

Celalettin

?brahim KOCAT?RK1, Ekrem Cengiz SEYHAN2, Mehmet Zeki

G?NL?O?LU1,

Nur ?RER3, Kamil KAYNAK4, Seyyit ?brahim D?N?ER1,

Mehmet Ali BED?RHAN1

1 Yedikule G???s Hastal?klar? ve G???s Cerrahisi E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi, 3. G???s Cerrahisi Klini?i,

?stanbul,

2 Yedikule G???s Hastal?klar? ve G???s Cerrahisi E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi, G???s Hastal?klar? Klini?i,

?stanbul,

3 Yedikule G???s Hastal?klar? ve G???s Cerrahisi E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi, Patoloji Klini?i, ?stanbul,

4 ?stanbul?niversitesi Cerrahpa?a T?p Fak?ltesi, G???s Cerrahisi Anabilim Dal?, ?stanbul.

?ZET

Primer pulmoner non-Hodgkin lenfoma: Literat?r de?erlendirmesiyle birlikte 10 olgu

Giri?: Primer pulmoner non-Hodgkin lenfoma (PPNHL) nadir g?r?len bir durumdur. Bu hastal???n klinik ?zellikleri, tedavi alternatifleri ve tedavi sonu?lar?n? a???a ??karmak i?in cerrahi olarak tan? konulmu? olgular?m?z? de?erlendirdik.??

Materyal ve Metod: Ocak 2004-Aral?k 2009 tarihleri aras?ndaki PPNHL olgular?yla ilgili geriye d?n?k bir g?zden ge?irme ?al??mas? yap?ld?. Demografik ve klinik bilgiler ortalama ve ortancalar ?eklinde verildi. Genel sa?kal?m Kaplan Meier y?ntemi kullan?larak hesapland?. Sa?kal?m oranlar? log rank testi kullan?larak kar??la?t?r?ld?. p de?erinin 0.05'in alt?nda olmas? durumu, anlaml?l?k d?zeyi olarak kabul edildi.???

Bulgular: Hastalar?n sekizi erkek ikisi kad?n olup, ortanca ya? 50 (aral?k 29-76) idi. Hastalar?n %40'?nda antijenik uyar?m, imm?ns?presyon veya otoimm?n hastal?k saptanmad?. T?m hastalar ba?vuru s?ras?nda semptomatik idi. Tan? i?in cerrahi i?lemler (dokuz kama rezeksiyon, bir pn?monektomi) gerekli oldu. Hastalar?n sekizinde mukoza ili?kili lenfoid dokunun ekstranodal marjinal zon lenfomas? (MALT lenfoma), ikisinde b?y?k B h?creli lenfoma bulundu. Hastalar; g?zlem (pn?monektomi yap?lan hasta), kemoterapi (n= 7), kemoterapi ve radyoterapi (n= 1) ile tedavi edildi. Be? y?ll?k sa?kal?m %76 idi. Bilateral ve unilateral hastal??? bulunan olgular?n sa?kal?m oranlar? aras?ndaki fark istatistiksel olarak anlaml? de?ildi.

Sonu?: Literat?r?n aksine PPNHL antijenik uyar?m olmadan da olu?abilir ve hastalar genellikle baz? semptomlar g?sterirler. PPNHL'nin tedavisi i?in kemoterapi veya cerrahi kullan?labilir. Hastalar?n sa?kal?m? iyidir.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Akci?er neoplazm?, lenfoma, non-Hodgkin

SUMMARY

Primary pulmonary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: ten cases with a review of the literature

Celalettin

?brahim KOCAT?RK1, Ekrem Cengiz SEYHAN2, Mehmet Zeki

G?NL?O?LU1,

Nur ?RER3, Kamil KAYNAK4, Seyyit ?brahim D?N?ER1,

Mehmet Ali BED?RHAN1

1 Clinic of 3rd Chest Surgery, Yedikule Chest Diseases and Chest Surgery Training and Research Hospital,

Istanbul, Turkey,

2 Clinic of Chest Diseases, Yedikule Chest Diseases and Chest Surgery Training and Research Hospital,

Istanbul, Turkey,

3 Clinic of Pathology, Yedikule Chest Diseases and Chest Surgery Training and Research Hospital,

Istanbul, Turkey,

4 Department of Chest Surgery, Faculty of Cerrahpasa Medicine, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey.

Introduction: Primary pulmonary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (PPNHL) of the lung occurs very rarely. To clarify clinical features, treatment alternatives and outcomes, we evaluated our surgically diagnosed PPNHL cases.

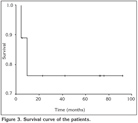

Materials and Methods: A retrospective review of PPNHL cases from January 2004 to December 2009 was performed. Demographic and clinical data are presented as means or medians. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival rates were compared using the log-rank test. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results: Patients were eight males and two females with a median age of 50 years (range, 29-76 years). In 40% of the patients, antigenic stimulation, immune-suppression or auto-immune disease could not been found. All patients were symptomatic at presentation. Surgical procedures were needed to obtain a diagnosis (nine wedge resections and one pneumonectomy). Eight patients had an extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma), and two had diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. The patients were treated with observation (pneumonectomy case), chemotherapy (n= 7), and chemotherapy and radiotherapy (n= 1). Five-year survival was 76%. Difference in survival rates of patients with bilateral vs. unilateral disease were not statistically different.

Conclusions: On contrary of the literature, PPNHL can occur with absence of antigenic stimulation, and patients generally have some symptoms. Chemotherapy or surgery can be used to treat PPNHL. Patient survival is good.

Key Words: Lung neoplasm, lymphoma, non-Hodgkin.

Geli? Tarihi/Received: 29/02/2012 - Kabul Edili? Tarihi/Accepted: 27/04/2012

Lymphomas, which are malignant tumors of lymphoid tissue, may rarely be detected as a form of primary lung disease, although they usually affect the lungs secondarily through hematogenous dissemination or direct invasion from hilar/mediastinal lymph nodes. Primary pulmonary lymphomas (PPL) represent < 1% of primary malignant lung tumors, < 1% of lymphomas and only 3-4% of extranodal lymphomas (1,2,3).

PPLs originate from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) (4). These tumors may be a type of Hodgkin's or non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL). The majority of PPLs consists of extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL), which are types of NHLs (5).

Pulmonary MALT lymphoma usually has an indolent course, remaining localized to the lung for long periods before dissemination. However, DLBCL is less frequent and is believed to have a poorer prognosis than MALT lymphoma (6,7).

Although some studies have reported this rare disease, the histopathological features, clinical course, optimal treatment, role of surgery, and prognostic factors are not well defined (8,9,10,11,12). In this study, we assessed the clinical, radiological, diagnostic, and pathological features of our cases with primary pulmonary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (PPNHL), along with prognosis and treatment results.

MaterialS and Methods

Our clinical (surgery clinic) database records were reviewed retrospectively, as we attempted to find patients with a diagnosis of PPNHL between January 2004 and February 2009. As this was a retrospective study, ethics committee acceptance not needed. Scientific Study Committee of our hospital reviewed and approved the database. We used the following criteria to diagnose PPNHL (10,13):

1. Unilateral or bilateral pulmonary involvement with NHL,

2. No evidence of mediastinal or hilar adenopathy,

3. No evidence of extrathoracic disease following a clinical staging work-up, which included a thorough physical examination, computed tomography (CT) scans (CT) of the chest, CT or ultrasonography of the abdomen and pelvis, gastroscopy, and an examination of bone marrow biopsy specimens,

4. No history of lymphoma,

5. No evidence of extrathoracic disease up to three months after the initial diagnosis.

Information on demographic variables, clinical and radiological findings, medical history, the procedures applied to patients to diagnose and treat, and histopathological findings of the tumors was gathered through the clinical database and patient files.

Physical examination findings did not contain any extrathoracic pathology. A thoracic CT scan was obtained for all patients. In those studies, no enlarged (> 1 cm in diameter) hilar or mediastinal adenopathy was found. Four patients underwent 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET).

The histological diagnosis of PPNHL was reviewed by a pathologist (NU). The diagnosis of PPNHL was based on the WHO criteria for characteristic histological and immunohistochemical features (4). After a histological diagnosis was obtained, the patients were evaluated by an oncologist. To ascertain the PPNHL diagnosis, abdominal and pelvic ultrasonograms (US) of all patients were monitored along with their gastroscopies and bone marrow biopsies, but no extrapulmonary lymphoma findings were discovered. Based on the oncologist's preference, the patients were continually supervised or underwent chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy.

All patients were supervised through physical examinations once per month for three months following the first histological diagnosis. At the end of the third month, patients with no extrapulmonary disease findings underwent thoracic CT and abdominal and pelvic US as a follow-up to this supervision, and the diagnosis of PPNHL was confirmed in these patients.

Patient follow-up was performed regularly through a physical examination and chest X-rays every three months, a thoracic CT every six months during the first year, a physical examination and chest X-ray every six months, and a thorax CT once per year in subsequent years. Supplementary reviews were also made whenever necessary. The physical examination findings and observation results were obtained from the clinical record system. Moreover, all patients were phoned and asked about their health status and the results of treatment.

Demographic and clinical data are presented as means or medians. Survival duration was measured from the time of diagnosis to the date of death or the last follow-up. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival rates were compared using the log-rank test. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

We identified 10 patients (eight males, two females) who fulfilled the criteria for a PPNHL diagnosis, with a median age of 50 years (range, 29-76 years). No patient had a history of lymphoma.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

At the time of diagnosis, all patients were symptomatic, and all patients had at least one pulmonary symptom. Four patients also had constitutional B symptoms (Table 1). The most frequently encountered symptoms were cough and chest pain, which were seen in 50% and 40% of the patients, respectively. Potential risk factors for developing the disease were found in two patients, namely diabetes mellitus type-I and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, each in one patient.

Radiological Characteristics

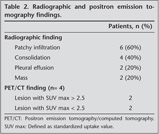

All patients had a chest roentgenogram and a chest CT. The most common radiological finding was localized infiltration or multiple patchy infiltrations (Table 2). Five patients presented with bilateral disease, and five had unilateral disease.

Diagnostic and Surgical Procedures

The mean period between the beginning of the symptoms and the diagnosis was approximately 62 days. All patients received a bronchoscopic examination. The bronchoscopic findings were bronchial edema in three patients and external compression in three. No other abnormal findings were seen in four patients. A bronchial lavage was performed in all patients, and a transbronchial needle aspiration biopsy was performed in three patients. However, the histopathological and microbiological examinations did not result in a diagnosis. After the chest CT identified a pulmonary lesion, five patients underwent CT guided percutaneous biopsies, none of which was diagnostic. Cytological and microbiological examinations of pleural effusions were also non-diagnostic.

A pathological diagnosis was established after surgical biopsies were obtained through video-assisted thoracoscopic wedge resection in one patient and an open thoracotomy in nine (wedge resection in eight, pneumonectomy in one). We removed all of the lesions in two patients (one pneumonectomy and one wedge resection). Based on a frozen section evaluation, the reason for the pneumonectomy was a centrally located tumor, suspicious of lung cancer, invading the adjacent lobe. Intraoperative sampling of mediastinal lymph nodes showed no metastases.

Histopathological Evaluation

Diffuse or nodular tumoral infiltration and lymphoepithelial lesions were seen in all specimens. The infiltration was heterogeneous in morphology and included tiny lymphocytes, monocytoid cells, immunoblasts, centrocyte-like cells, plasma cells, rarely centrocytes, and lymphoepithelial lesions in the specimens of eight patients. The infiltration invaded the bronchi, bronchioles, and alveolar septa (Figure 1). In the immunohistochemical study, pancytokeratin was (-), LCA and CD 20 were diffusely (+), and CD3 and CD5 staining were weak. These cases were diagnosed as MALT lymphoma.

In two of the cases, we detected diffuse and nodular infiltration that distorted the cellular structure and that were characterized by blastic lymphoid cellular proliferation with large nuclei (Figure 2). We also detected that pan-cytokeratin was (-), leukocyte common antigen (LCA) and CD20 diffusely (+). Additionally, bcl-2 was (+), and the Ki67 proliferative index was high, also reactive lymphocites expressed CD3 (+). These findings led to a diagnosis of DLBCL.

Treatment

Eight patients received chemotherapy (radiotherapy in one), and the chemotherapy regimen was CHOP or R-CHOP. Two patients did not receive chemo or radiotherapy (pneumonectomy performed, and HIV infected patients) (Table 3).

Follow-up and Survival

There was no operative death but one hospital mortality. The median follow-up time was 42 months (range, 4-92 months). The patient who had an HIV infection and did not receive chemotherapy was lost at follow-up on the 5th month follow-up was completed for nine patients.

Two patients died from the disease during the follow-up period. Local recurrence was seen in one patient four years after the diagnosis. This patient had a recurrent episode and was treated with chemotherapy (DHAP regimen). The five-year survival rate was 76% (Figure 3). No significant difference in survival was determine between those with bilateral or unilateral disease (p= 0.98). The long-term outcomes in this series of patients are listed in Table 3.

Discussion

A commonly used set of criteria for PPL proposed by L'Hoste et al. is lymphoma with (14):

a. Involvement of the lung, lobar, or primary bronchus, with or without mediastinal involvement and

b. No evidence of extrathoracic lymphoma at the time of diagnosis or for three months there after.

A pulmonary lymphoma might originate in the lungs (PPL).

According to the Ann Arbor system, which is frequently applied for lymphoma staging, a pulmonary lymphoma with only lung involvement is classified as stage 1 (15). PPLs can attack hilar, mediastinal or subdiaphragmatic lymph nodes and adjacent and distant organs during their course. In the case of pulmonary lymphoma with hilar and mediastinal lymph involvement, it may be a primary pulmonary lymphoma in higher stages or it may originate from hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes attacked the lung (secondary pulmonary lymphoma). Therefore, a pulmonary lymphoma should not be defined as PPL when a patient is diagnosed during hilar and mediastinal lymph involvement. From this point of view, not all NHLs with lung tissue involvement, but only ones without hilar and mediastinal lymph node involvement (stage 1) were accepted as PPNHL, and these cases were included in the study. Approximately 2500 patients per year are diagnosed with lung cancer in our hospital's participating clinics to this study. Considering this number, the PPL frequency among patients diagnosed with lung cancer over six years was calculated as 0.6%.

This rate confirms the low level of PPL frequency.

The incidence of PPNHL peaks in the sixth and seventh decades of life, and the ratio of males to females is close to 1 (5). Few patients are under the age of 30 years (12). The observation that we had patients in their 20s and 30s and that the number of male patients as high differed from the literature. These discrepancies probably indicate that the basic characteristics of this disease have not yet been thoroughly revealed.

Most investigators believe that MALT is not a normal constituent of the human bronchial tree but rather is acquired in response to long-term exposure to various antigenic stimuli such as smoking, infection, or autoimmune disease (16). Immunosuppression is also a known risk factor for developing lymphoma (17). Hence, lymphomas stemming from MALT are formed as a result of antigenic stimulation or immunosuppression. In our series, the observation that immunosuppression, infection, smoking, auto-immune disease, or chronic antigenic stimulation was detected in 60% of patients. Because of smoking, autoimmune disease, or chronic antigenic stimulation was not detected in the remaining patients suggests that it is probable that another unknown factor that triggers these conditions causes PPNHL pathogenesis.

PPNHL has various clinical symptoms. However, symptoms and physical signs are nonspecific and contribute little to the diagnosis. It has been reported that 37.5-50% of patients are asymptomatic (10,18). However, in our series, no patient was asymptomatic.

Moreover, the rate of constitutional symptoms in our series was higher than the reported rate (25%) for PPLs in the literature (6,19). The lack of symptom in PPNHL cases may be because patients are not examined thoroughly, which may wrongly result in patients being labeled as asymptomatic. Symptoms are usually detected when patients are examined thoroughly.

A decrease in respiratory sounds or crackles during auscultation and dullness during percussion may rarely be detected, whereas these findings are common during the physical examination of a patient with PPL (6). Seventy percent of our cases had normal physical examination findings.

Although acute-phase reactants (sedimentation, C-reactive protein) are high, these findings are not specific to patients with PPNHL. Furthermore, blood lactate dehydrogenase levels are generally high, as expected in patients with lymphomas, but do not provide specific data.

Radiological abnormalities in the lung parenchyma may indicate a lymphoma. Despite that opacities or nodules have been reported as a frequent sign in other series, patchy infiltration and consolidation were the most commonly encountered radiological findings in our series (5,6,20). Our findings showing that infiltrates or consolidation occurred in 90% of patients concur with findings for PPNHL. Mass lesion or pleural effusion (two patients for each) may also be found in some cases (21). Thus, the roentgenographic appearance is variable and can only suggest the possibility of lymphoma.

FDG-PET has been regarded as the gold standard for lymphoma imaging (22). However, insufficient data are available about the use of FDG-PET for primary pulmonary lymphomas. A preoperative FDG-PET study was available for four of our cases. The maximum level of FDG uptake was < 2.5 in two of the patients and between 2.5 and 5 in the other two patients. These results show that PPL has low FDG involvement. Hence, the benefit of FDG-PET is speculative in the clinical assessment of PPL.

Patients with PPNHL are usually evaluated through less invasive methods before surgical methods are used to obtain samples. However, these methods are unlikely to be successful. Bronchoscopy may be of limited value, as diagnosis based on endobronchial changes is rare (9,10). In one series, 83% of patients underwent a bronchoscopy, but only 30% who underwent a direct biopsy or tracheobronchial biopsy received a diagnosis, and the remaining large patient group (66.7%) required surgery for a diagnosis (9). The positive predictive rate of a puncture biopsy under CT guidance is only 25% (8).

PPL is generally diagnosed through an evaluation of large surgical tissue biopsies (9).

Pre-surgical studies failed to lead to a PPL diagnosis in our series. Some new diagnostic methods (immunohistochemical and gene re-arrangement studies, cell marker studies, and molecular techniques such as flow cytometry applied to material obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage) are believed to be effective for diagnosis (23). However, their efficacy has not yet been demonstrated. The difficulty in diagnosing the disease results in a long period between the emergence of symptoms and the diagnosis (6).

PPL might be of various histopathological types. The most frequently encountered type (80-90%) is the MALT lymphoma whereas a DLBCL is less frequent (24). MALT lymphoma usually occurs in immunosuppressed patients (17). Although we evaluated a small number of patients, we compared the demographic and clinical characteristics of those with MALT lymphoma and those with DLBCL. No significant differences were observed in the demographic features, the mode of presentation, or the biochemical measures. Our patients with DLBCL have also no history of immuncompromising disease.

The natural history of PPNHL appears to be slow compared with that of other low grade lymphomas, and treatment is controversial (7,9,10,19,24,25). Some investigators advocate no therapy because of its indolent course (24). One retrospective cohort analysis reported 11 patients with MALT lymphoma of the lung who did not undergo treatment following initial diagnosis. The median observation time without therapy was 28.1 months. Within this time, all 11 patients showed at least stable disease (26). This result suggests that MALT lymphoma of the lung is a very indolent disease with the potential for spontaneous regression. While most authors recommend surgery, chemotherapy alone or with surgery is useful for treating PPNHL (24,25). Some recent series did not demonstrate any difference in survival among patients receiving surgery, chemotherapy, or a combination (7,9,10,19). However, treatment was not always detailed, and the follow-up varied according to the series. Patients with localized PPL may be cured with local-regional therapy alone (surgical intervention or irradiation). Frequently, a diagnostic biopsy (by wedge resection or lobectomy) resects the entire lesion. If the pathological diagnosis is MALT lymphoma without evidence of higher-grade transformation and staging finds no disease elsewhere, a complete resection may be considered definitive, and no further therapy is required (9). If residual or multifocal lung disease or disease in the contralateral chest is evident, either chemotherapy or radiotherapy (if the lesion is localized) may be considered (27,28). Due to the risk of more aggressive progression of non-MALT lymphoma pulmonary lymphomas, histopathological type is also significant in the choice of treatment although data concerning this issue are limited (13,21,28). More aggressive chemotherapy regimens may be considered for recurrent disease, as we did in one patient. Additionally, some authors still suggest more aggressive chemotherapy in the event of bilateral disease (24,25).

Diagnostic tissue can be obtained through surgery when managing PPL and a therapeutic resection can be performed. Tumors appearing resectable should be approached with intent to cure by performing a complete surgical resection. Some investigators believe that surgery should be the treatment of choice if a complete resection can be achieved. A complete resection was associated with a 10-year survival rate of almost 90% in one series (11). In patients with a large, nonresectable lesion or with bilateral disease, obtaining sufficient tissue for a diagnosis of lymphoma is the goal of the surgery. A limited wedge resection or an incisional biopsy is appropriate in these patients. When considering an indeterminate resectable lung mass during a thoracotomy, the surgeon's primary concern is bronchogenic carcinoma. If a complete resection is possible in an otherwise healthy patient, this resection should not be compromised, and obtaining negative margins should be the main objective. Although some have recommended a pneumonectomy for multiple lesions of low grade PPL involving one lung, this option may be too aggressive given the indolent course of the disease (11). In our series, in a single case in which a pneumonectomy was conducted, the reason for this comprehensive resection was that the diagnosis of a bronchogenic carcinoma had been reported based on the frozen section examination. This patient did not undergo adjuvant chemotherapy and is still alive.

The behavior and natural history of pulmonary MALT lymphoma is similar for diseases in different organ systems (29). Patients with PPNHL, even if not be treated, have a good survival rate (50% to 70% at 10 years) (5,6). Interestingly, surgical treatment, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or combinations of these strategies all seem to achieve good results (19). However, studies are not comparable with respect to the variety of treatments and limited number of patients. Prognostic factors influencing survival and the optimal therapy for MALT lymphoma have not been clearly defined. One of the probable factors that may affect survival is histopathological type. Although some studies have determined a poorer prognosis for patients with non-MALT lymphoma, no survival difference has been found between patients with MALT lymphoma and those with non-MALT lymphoma (5,7,8,9,10,13,28). Age, gender, auto-immune disorders, monoclonal gammopathy, extent of the disease within the lungs, pleural involvement, and positive lymph nodes are not prognostic factors (13).

In contrast to known, we found that, primary NHL of the lung generally cause nonspecific respiratory symptoms, and in about half of the patients an etiologic factor could not been detected. Surgery provides a diagnosis in all instances and provides a definite therapy for many patients. Specific prognostic factors could not be identified in our study.

Overall, these lymphomas are associated with a good prognosis. Further clinical experience and long-term follow-up are needed to identify the prognostic factors.

CONFLICT of INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Miller DL, Allen MS. Rare pulmonary neoplasms. Mayo Clin Proc 1993; 68: 492-8. [?zet]

- Rosenbery SA, Diamond HD, Jaslowitz B, Craver LF. Lymphosarcoma: a review of 1269 cases. Medicine 1961; 40: 31-84.

- Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer 1972; 29: 252-60.

- WHO classification ot tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW (eds). WHO Press; Lyon, 2008: 214-8 and 233-8.

- Li G, Hansmann ML, Zwingers T, Lennert K. Primary lymphomas of the lung: morphological, immunohistochemical and clinical features. Histopathology 1990; 16: 519-31. [?zet]

- Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Nichols PW, Wehunt WD, Lazarus AA. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and pseudolymphoma of lung: a study of 161 patients. Hum Pathol 1983; 14: 1024-38. [?zet]

- Cordier JF, Chilleux E, Lauque D, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Dietemann-Molard A, Dalphin JC, et al. Primary pulmonary lymphomas: a clinical study of 70 cases in nonimmunocompromised patients. Chest 1993; 103: 201-8. [?zet]

- Graham BB, Mathisen DJ, Mark EJ, Takvorian RW. Primary pulmonary lymphoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2005; 80: 1248-53. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Kim JH, Lee SH, Park J, Kim HY, Lee SI, Park JO, et al. Primary pulmonary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2004; 34: 510-4. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Ferraro P, Trastek VF, Adlakha H, Deschamps C, Allen MS, Pairolero PC. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the lung. Thorac Surg 2000; 69: 993-7. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

-

Eynden FV, Fadel E, de Perrot M, de Montpreville V, Mussot S, Dartevelle P.

Role of surgery in the treatment of primary pulmonary B-cell lymphoma. Ann

Thorac Surg 2007; 83: 236-40.

[?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF] - Xu HY, Jin T, Li RY, Ni YM, Zhou JY, Wen XH. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Chin Med J 2007; 20: 648-51. [?zet]

- Kurtin PJ, Myers JL, Adlakha H, Strickler JG, Lohse C, Pankratz VS, et al. Pathologic and clinical features of primary pulmonary extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type. Am Surg Pathol 2001; 25: 997-1008. [?zet]

- L'Hoste RJ, Fillipa DA, Lieberman PH, Bretsky S. Primary pulmonary lymphoma. A clinicopathologic analysis of 36 cases. Cancer 1984; 54: 1396-406. [?zet]

- Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, Smithers DW, Tubiana M. Report of the Committee on Hodgkin's Disease Staging Classification. Cancer Res 1971; 31: 1860-1. [?zet]

- Nicholson AG, Wotherspoon AC, Diss TC, Hansell DM, Du Bois R, Sheppard MN, et al. Reactive pulmonary lymphoid disorders. Histopathology 1995; 26: 405-12. [?zet]

- Rabkin CS, Yellin F. Cancer incidence in a population with a high prevalence of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Natl Cancer Inst 1994; 86: 1711-6. [?zet]

- Poletti V, Romagna M, Gasponi A, Baruzzi G, Allen KA. Bronchoalveolar lavage in the diagnosis of low-grade, MALT type, B-cell lymphoma in the lung. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 1995; 50: 191-4. [?zet]

- Habermann TM, Ryu JH, Inwards DJ, Kurtin PJ. Primary pulmonary lymphoma. Semin Oncol 1999; 26: 307-15. [?zet]

- Lewis ER, Caskey CI, Fishman EK. Lymphoma of the lung: CT findings in 31 patients. AJR 1991; 156: 711-4. [?zet] [PDF]

- Cardinale L, Allasia M, Cataldi A, Ferraris F, Parvis G, Fava C. CT findings in primary pulmonary lymphomas. Radiol Med 2005; 110: 554-60. [?zet]

- Yamamoto F, Tsukamoto E, Nakada K, Takei T, Zhao S, Asaka M, et al. 18F-FDG PET is superior to 67Ga SPECT in the staging of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Nucl Med 2004; 18: 519- 26. [?zet]

- Rodr?guez de Castro F, Molero T, Juli?-Serd? G, Caminero J, Cabrera P. DNA analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage in the diagnosis of pulmonary lymphoma. Respiration. 1995; 62: 359-60. [?zet]

-

Cadranel J, Wislez M, Antoine M. Primary pulmonary lymphoma. Eur Respir J

2002; 20: 750-62.

[?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF] - Addis BJ, Hyjek E, Isaacson PG. Primary pulmonary lymphoma: a re-appraisal of its histogenesis and its relationship to pseudolymphoma and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia. Histopathology 1988; 13: 1-17. [?zet]

- Troch M, Streubel B, Petkov V, Turetschek K, Chott A, Raderer M. Does MALT lymphoma of the lung require immediate treatment? An analysis of 11 untreated cases with long-term follow-up. Anticancer Res 2007; 27: 3633-7. [?zet] [PDF]

- Sarna GP, Kagan AR. Extranodal lymphomas. In: Haskell CM (ed). Cancer Treatment. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1995: 1043-50.

- Fisher RI, Dahlberg S, Nathwani BN, Banks PM, Miller TP, Grogan TM. A clinical analysis of two indolent lymphoma entities: mantle cell lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma (including the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue and monocytoid B-cell subcategories): a Southwest Oncology Group study. Blood 1995; 85: 1075-82. [?zet] [PDF]

- Thieblemont C, de la Fouchardiere A, Coiffier B. Nongastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas. Clin Lymphoma 2003; 3: 212-24. [?zet]

Yaz??ma Adresi (Address for Correspondence):

Dr. Celalettin ?brahim KOCAT?RK,

Yedikule G???s Hastal?klar? ve

G???s Cerrahisi E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi,

3. G???s Cerrahisi Klini?i, ?STANBUL - TURKEY

e-mail: celalettinkocaturk@hotmail.com