Akci?er kanseri tan?s?n?n bildirilmesinde ilgililerin e?ilimleri:

Sosyal k?s?tlamalar, ?e?itli kliniklerdeki t?bbi uygulamalar

Sibel DORUK1, Can SEV?N?2, Fidan SEVER3, Oya ?T?L2, Atila AKKO?LU2

1 Gaziosmanpa?a ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi, G???s Hastal?klar? Anabilim Dal?, Tokat,

2 Dokuz Eyl?l ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi, G???s Hastal?klar? Anabilim Dal?, ?zmir,

3 ?ifa ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi, G???s Hastal?klar? Anabilim Dal?, ?zmir.

?ZET

Akci?er kanseri tan?s?n?n bildirilmesinde ilgililerin e?ilimleri: Sosyal k?s?tlamalar, ?e?itli kliniklerdeki t?bbi uygulamalar

Giri?: ?al??man?n amac?, akci?er kanserli bir hastaya tan?n?n s?ylenmesine ili?kin ilgili kesimlerin g?r??lerini belirlemek, hastanemizdeki uygulamay? de?erlendirmektir.

Materyal ve Metod: Kanser hastalar?n?n takip edildi?i b?l?mlerde ?al??an hem?irelere ve doktorlara, 4-6. s?n?ftaki t?p fak?ltesi ??rencilerine, kanser ve kanser d??? hastal??? olan hastalar?n yak?nlar?na haz?rlanan anket uyguland?.

Bulgular: ?al??maya ya? ortalamas? 28 y?l olan 228'i kad?n 347 olgu al?nd? (64 doktor, 100 hem?ire, 61 t?p fak?ltesi ??rencisi, 122 hasta yak?n?). Doktorlar?n %62.5'i, hem?irelerin %53.2'si, t?p fak?ltesi ??rencilerinin %59'u, hastas? akci?er kanseri olan hasta yak?nlar?n?n %45.9'u, hastas?n?n kanser d??? hastal??? olan hasta yak?nlar?n?n %52.5'i kanser tan?s?n?n hastaya s?ylenmesi gerekti?ini d???n?yordu. Doktorlar?n %29.5'i hastalar?na kanser tan?s?n? s?yl?yordu. Doktorlar?n g?r??lerine ve klinik uygulamalar?na cinsiyet, ya?, yurt d??? deneyim, akademik kariyer, uzmanl?k b?l?m? ve mesleki deneyim s?resinin etkisi saptanmad?.?

Sonu?: Kanser hastas?n?n hastal???na ili?kin bilgi edinme hakk?n? doktorlar?n ?al??madaki di?er gruplara g?re daha fazla ?nemsedi?i saptanm??t?r. Genellikle doktorlar kanser tan?s?n?n hastaya s?ylenmesi gerekti?ini d???nse de bu g?r??leri klinik uygulamalar?na yans?mamaktad?r.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Akci?er kanseri, kanser tan?s?n?n a??klanmas?.

SUMMARY

The trends of relevance about telling lung cancer diagnosis: social constraints, medical practice in several clinics

Sibel DORUK1, Can SEV?N?2, Fidan SEVER3, Oya ?T?L2, Atila AKKO?LU2

1 Department of Chest Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Gaziosmanpasa University, Tokat, Turkey,

2 Department of Chest Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey,

3 Department of Chest Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Sifa University, Izmir, Turkey.

Introduction: The aim of this study is to assess the opinions of relatives about telling the lung cancer diagnosis to the patient and evaluate the implementation in our hospital.

Materials and Methods: A survey questionnaire was designed, and applied on nurses and physicians working in oncology care units, 4th-6th grade medical students, and relatives of cancer and non-cancer patients.

Results:? Totally 347 (228 males, 119 females) participants (64 physicians, 100 nurses, 61 medical students, and 122 relatives of patients) with a mean age of 28 were enrolled in the study. 62.5% of doctors, 53.2% of nurses, 59.5% of medical students and 45.9% of relatives of lung cancer patients thought that the patient should be informed about his/her cancer diagnosis. 29.5% of the physicians told their patients about their diagnosis of cancer.? Gender, age, abroad experience, academic career, speciality, and period of professional experience were not determined to have any impact on physician's opinion and clinical practices.

Conclusion: It was determined that physicians care more about patients' right to be informed than other participating groups. Generally, although physicians agree that the diagnosis of cancer should be told to the patient, their routine clinical practices do not reflect this viewpoint.

Key Words: Disclosure of cancer diagnosis, lung cancer.

Geli? Tarihi/Received: 09/05/2012 - Kabul Edili? Tarihi/Accepted: 13/08/2012

Introduction

Cancer is a life-threatening disease and in many cultures it has been perceived as incurable (1,2). Lung cancer comprises 15% of cancer cases and 31% of all cancer deaths and the incidence has been increasing (3). At the time of diagnosis, more than 60% of the cases are in the advanced stage and also five year life expextancy is lower than 20% (4,5).

Disclosure of cancer diagnosis and prognosis to patients has been a matter for debate among health care professionals (6). Patients, families and physicians are three essential components in the diagnosis of cancer. Generally, relatives of the patients are more efficient on informing the patient about his/her cancer diagnosis. The disclosure of a patient's cancer diagnosis is a process that involves health care professionals, patients and their families (7). Consequently, many health care professionals consider the disclosure of cancer as a difficult task (8,9,10). It is extremely difficult to decide to tell the patient that they had a fatal disease like lung cancer (11). Despite the global trend considering to provide more information to patients, nondisclosure is still the most frequently preferred in many countries (7, 12). From one culture to another, answers to the question of "Should the patients be informed about their diagnosis?" question is extremely different. There is a high diversity among different cultures' view on the issue of to what extent patients should be informed (13). There are differences among countries' regarding of the way of disclosure (1). Today, direct disclosure of cancer to the patient has become the norm in many Western countries (14,15,16). In contrast, the disclosure of a cancer diagnosis to the patient remains an uncommon implementation in a large number of non-Western countries (17,18). Frequently, family members do not wish their patient to be informed about the cancer diagnosis. The physicians, in line with the wishes of the family members, inform the patient insufficiently and family members are usually the informed ones because they believe that this will cause psychological detorioration in their patient (9,11,19,20). It is very common among health care professionals and patients' relatives to belive that limited information contributes to the better emotional state of patients, but studies do not support this assumption (21). In the past, the physicians supposed that they made the most realistic decisions about their patients; however, recently in developed countries, properly informed patient has been involved in the decision-making process (12). In the studies conducted in the last 40 years, the importance of cultural diversities, with respect to realistic approaches for providing diagnostic information to the patient, has been emphasized (22). In Turkey, the prevailing trend is to conceal diagnostic information from the cancer patient. Generally, Turkish physicians inform a family member rather than the patient about cancer diagnosis? (9,19).

The aim of this study is to determine the viewpoints of physicians, medical students, nurses in the relevant specialities and also relatives of cancer and non-cancer patients and evaluate the clinical practice in our hospital.

MATERIALS and Methods

Staff physicians with at least one-year professional experience in the departments of internal medicine, chest diseases, psychiatry, medical oncology and thoracic surgery, nurses working in the above-mentioned departments, 4th-6th grade medical students, relatives of cancer and non-cancer patients were included in the study.

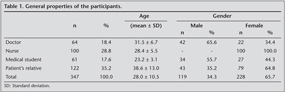

Thirty hundred and forty seven cases (female/male 228/119) with a mean age of 28.0 ? 10.5 (18-65) years were included in the study. A 13-item survey questionnaire was conducted to all participants in face-to-face interview sessions. All participants were asked "Should the lung cancer diagnosis be told to the patient?" and also they were asked if they want to be informed about their diagnosis of lung cancer. The physicians were asked "Do you inform your patients about cancer diagnosis?" and about their attitude in clinical practice.

The obtained data were analyzed using SPSS/Win 15.0 software program. To determine differences among groups chi-square and student's t-test were used. p≤ 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

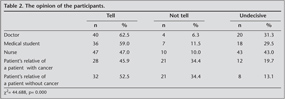

The general properties of the cases can be seen in Table 1. The opinion of the participants about revealing the diagnosis to the lung cancer patients have been shown in Table 2. 34.4% of the patients' relatives and 6.3% of the physicians approved that cancer patients' have right to know the diagnosis (p= 0.000).

The distribution of the clinics of 64 physicians was as follows: internal medicine disciplines including chest diseases, internal diseases, and psychiatry (n= 36; 56.3%), radiation/medical oncology (n= 19; 29.7%) and thoracic surgery (n= 9; 14.1%). Eighteen physicians (29.5%) informed their patients about cancer diagnosis. Gender, abroad experience, academic career and professional field had no effect on the opinion and clinical practice of the physician's.

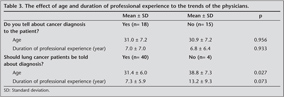

The effects of age and period of professional experience of the physicians revealing of diagnosis to their lung cancer patients can be seen in Table 3. Mean age of the physicians considering necessity of telling the truth to the cancer patients was higher than those sustaining the opposite viewpoint (p= 0.027). The impact of professional experience duration on perspectives, and clinical practice related to the disclosure of diagnosis to the cancer patient could not be demonstrated (p= 0.073, and p= 0.993).

Fifthy eight of the physicians said that ?I want to be informed if I would be cancer' while 2 of them reported that ?I do not want to be informed'. The physicians responded to the question ?Do you want your father, mother or a familiar to be informed of their cancer diagnosis?' as follows:

- I would leave the decision to his/her physician (n= 32; 50.0%);

- I definitively don't want them to be told about the diagnosis (n= 6; 9.4%), and

- I would reveal the diagnosis myself (n= 26; 40.6%).

Forty-seven (47.0%) of 100 the nurses had opinions favoring the necessity of telling the diagnosis to their patients, while others were against (n= 10; 10.0%) or undecisive (n= 43; 43.0%) about the suggestion. The impact of mean ages and duration of professional experience of the nurses on their opinions about informing the patient of the cancer diagnosis could not be demonstrated (p= 0.852 and 0.786, respectively).

When opinions of participating healthcare professionals (nurses and physicians, n= 164) and the other participants (patients' relatives; n= 122) about the necessity of informing the cancer patients about the diagnoses were compared, a significant difference was defined between the groups (p= 0.000). Eighty seven of healthcare professionals (53.0%) were in favour of their against (n= 14; 8.5%) the disclosure of the diagnosis to the patient. The corresponding rates of patients' relatives were 49.2% (n= 60), and 34.4%, respectively.

Twenty-eight of 61 (45.9%) relatives of the lung cancer patients responded affirmatively to the question ?Should the cancer diagnosis be told to the patient?', while 21 (34.4%) of them were against this view. Twelve of them (19.7%) were undecisive. However some relatives of non-cancer patients responded to the above question favorably (n= 21; 34.4%), while others were against (n= 61; 52.5%) or undecisive (n= 8; 13.1%) (p= 0.587).

Thirty-seven relatives (60.7%) of cancer patients responded affirmatively to the question ?Does your cancer patient know that he/she is cancer?' it was found that cases who were cognizant of their cancer diagnosis got that information from their physicians (n= 24 cases; 64.9%), their relatives (n= 5), and medical files (n= 4) and four cases felt that they had cancer. In conclusion, 24 (39.3%) of 61 lung cancer patients were informed by their physicians. Nineteen (94.7%) of 24 relatives of cancer patients who did not know their diagnoses replied to the question "Why does not your patient know his/her diagnosis?" as they did not absolutely want their patients to know the diagnosis.

Discussion

Since, at the time of diagnosis, majority of the cases have advanced stage disease and lower rates of 5-year life expectancy, telling the patient that he/she has lung cancer is a very difficult decision (4,5,11). Physicians usually do not inform their cancer patients adequately about their diagnosis in order to prevent the patient from psychological trauma in case of disclosure and also in compliance with the wishes of the family members (8,22). In a conference organized by ?International Union Against Cancer' (UICC), "complete or partial concealment of the truth about the diagnosis" was found to be prevailing (12).

The approach of the physicians about disclosure of the diagnosis to the cancer patients varies among different geographical and cultural regions and also in time. The attitudes of the physicians in the North America and Europe towards informing the cancer patients about their diagnoses have changed substantially within the last 30 years. Majority of the physicians in the USA did not inform their patients about the diagnosis before 1960, however as a known fact, this approach has changed in recent years (12,23). In East European countries and Japan, physicians usually do not provide information to their patients about their disease and its poor prognosis (23). In Asia, many physicians generally do not inform the patients about the diagnosis (17,24). Research has demonstrated that a large proportion of cancer patients in the Middle East are not informed about their diagnosis (19,25,26,27). Although in a survey questionnaire conducted in Japan in 1991, patient's right to be notified by the clinicians has been conceptually accepted, it has been established in clinical practice that only 13% of the patients have been told of their diagnoses and generally patient's relatives have been notified (28).

Many reports indicate that families show resistance to the disclosure of the diagnosis to cancer patients (11,19,20). A previous research in non-Western countries suggests that the main reason for non-disclosure of cancer diagnosis by health care providers is patients' family members who discourage and prevent health care providers from disclosing this information (7,19,29,30). Generally, in Turkey, physicians think that family members do not want their cancer patients to be informed about their diagnosis, and thus Turkish physicians prefer to disclose the diagnosis to a family member (19). Ozisik et al. reported the corresponding percentage as 83.9% (31). Although most of the doctors included into the study say that the cancer diagnosis should be told to the patients it was understood that their clinical practice is not in this direction from both their own words and the cancer patients' relatives words.

In a study carried out with the aim of determining the opinions of European gastroenterologists about revealing the diagnosis of cancer to the patient, it was established that in Northern Europe, the patient has been informed about the diagnosis, while in Southern Europe it has been concealed from the patient (32). It was established that in USA, only 2% of oncologists did not inform their cancer patients about the diagnosis (33). In a study performed in Portugal, it was reported that 71% of oncologists revealed the diagnosis to their cancer patients (34). Ozdogan et al. reported that a notable percentage of Turkish oncologists never or hardly ever disclosure the cancer diagnosis to their patients (35). As evaluated in our study, only 10.5% of the oncologists have informed their cancer patients about the diagnosis.

In Samur et al.'s study, it was revealed that 63.0% of cancer patients did not know their diagnoses (36). In Iran 37%-65% of cancer patients do not know their diagnosis (37,38,39). In our study which has been based on the information provided by patients' relatives, 60.7% of the patients has known their diagnoses. We should indicate that 64.9% of the cancer patients who know the diagnosis and 39.3% all of the cancer patients were told about their cancer diagnosis by his/her doctor.

Iranian physicians and nurses believed that less than 20% of cancer patients were told about their diagnosis (40). Despite the common practice of non-disclosure, there is initial evidence that many Iranian cancer patients, in fact, want to be informed abaout their diagnosis (37).

Accordance with the literature findings a majority (89.5%) of the physicians in the study indicated that they would want to be informed about the diagnosis if they had cancer (31,36).

In a questionnaire survey conducted among medical students, the proportion of the first grade medical students who were in favour of disclosing the diagnosis to the patient was higher when compared with the 6th grade internists (41). In our study 59.0% of the medical students think that cancer diagnosis should be told to the patients while in Elger et al. study 72.4% of the medical students accepted this perspective (23). Even though insignificant differences existed between medical students of different grades, it was found that the proportion of those in favour of disclosing the diagnosis to the patient was higher among 6th grade students.

It is common among health professionals and patients' relatives to believe that limited information contributes to the better emotional state for patients, however studies don't support this idea (21). Atesci et al. suggest that awareness of cancer diagnosis correlates with higher prevalence of psychological morbidity. They mentioned that psychological trauma can be common in patients who were not informed by their doctor and they suggest a change in practice of non disclosure in Turkey (42). Noore et al. reported that nearly one-third of their cancer patients be informed by a family member, a relative or a friend (43). Our study determined that 13.5% of cancer patients learned about the diagnosis from their relatives.

In spite of differences between the countries, it was reported that healthy adults and cancer patients want to know the truth about their diagnoses and prognosis (23,43,44,45,46,47,48,49). In our study since nearly one third of the relatives of the cancer patients stated that "they absolutely don't want their patients to be informed about the diagnoses", we didn't included particularly "cancer patients" in this study.

A number of the patients, family members and physicians believed the disclosure of cancer was dangerous. The use of the word ?cancer' itself was believed to have considerable negative effects on the patients (50).

Sheu et al. reported that 28.0% of the patients' relatives wanted to be the primary person who has been informed about the cancer diagnosis (51). It has been emphasized that, in Japan and China, the decision of the family is effective in informing the patient about his/her cancer diagnosis. It was established that, in Singapore, 90.4% of the physicians have been informing patient's family about the diagnosis (47,52,53). In our study 34.4% of all relatives of the patients were against informing the patient. In another study carried out in our country, 87.4% of the patients's relatives stated that the diagnoses should be told to them (19).

In a study carried out in our country it was reported that 64% of the nurses shared the opinion that patients should be told the truth (54). In another study, aproximately 80% of the nurses were found in favor of disclosing the truth to a cancer patient (55). It was reported in Li et al's study, 81.4% of the nurses thought that the truth should be told to the patients in early stage, but this ratio was 44.2% for terminal stage patients (56). Demirsoy et al. also have evaluated the nurses and they reported that 90% of them thought that patients should be informed about the diagnosis (57). In our study, only 47% of the nurses thought that the diagnosis should be told to the patients and a large proportion of them were undecisive.

In this study the opinion of the health care professionals, patients' relatives and medical students about telling the truth to the patient his/her cancer diagnosis were evaluated. It was demonstrated that mostly physicians take care about cancer patients' rights to obtain information about their disease when compared with other health care professionals. Although physicians think that they should inform their patients about their cancer diagnosis, this perspective do not reflect in their clinical practice. Although most of the doctors included into the study say that the cancer diagnosis should be told to the patients, it has been understood that their clinical practice is not in this direction Besides, we thought that the information about our clinical practice will contribute to our country data.

CONFLICT of INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Kazdaglis GA, Arnaoutoglou C, Karypidis D, Memekidou G, Spanos G, Papadopoulos O. Disclosing the truth to terminal cancer patients: a discussion of ethical and cultural issues. East Mediterr Health J 2010; 16: 442-7.

- Stark DP, House A. Anxiety in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2000; 83: 1261-7.

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer Statistics, 2007. Cancer J Clin 2007; 57: 43-66.

- Goksel T, Akkoclu A; Turkish Thoracic Society, Lung and Pleural Malignancies Study Group. Pattern of lung cancer in Turkey, 1994-1998. Respiration 2002; 69: 207-10.

- Jett JR, Midthun D. Screening for lung cancer: current status and future directions. Chest 2004; 125: 1588-628.

- Shahidi J. Not telling the truth: circumstances leading to concealment of diagnosis and prognosis from cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care 2010; 19: 589-93.

- Benson J, Britten N. Respecting the autonomy of cancer patients when talking with their families: qualitative analysis of semistructured interviews with patients. BMJ 1996; 313: 729-31.

- Espinosa E, Gonzalez BM, Zamora P, Ordonez A, Arranz P. Doctors also suffer when giving bad news to cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 1996; 4: 61-3.

- Ozdogan M, Samur M, Bozcuk HS, Coban E, Artac M, Savas B et al. "Do not tell": what factors affect relatives' attitudes to honest disclosure of diagnosis to cancer patients? Support Care Cancer 2004; 12: 497-502.

- Sinclair CT. Communicating a prognosis in advanced cancer. J Support Oncol 2006; 4: 201-4.

- Miyata H, Takahashii M, Saito T, Tachimori H, Kai I. Disclosure preferences regarding cancer diagnosis and prognosis: to tell or not to tell? J Med Ethics 2005; 31: 447-51.

- Surbone A. Telling the truth to patients with cancer: what is the truth? Lancet Oncol 2006; 7: 944-50.

- Surbone A. Persisting differences in truth telling throughout the world. Support Care Cancer 2004; 12: 143-6.

- Hoff L, Tidefelt U, Thaning L, Hermer?n G. In the shadow of bad news-views of patients with acute leukaemia, myeloma or lung cancer about information, from diagnosis to cure or death. BMC Palliat Care 2007; 6: 1.

- Salander P. Bad news from the patient's perspective: an analysis of the written narratives of newly diagnosed cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 2002; 55: 721-32.

- Wood WA, McCabe MS, Goldberg RM. Commentary: disclosure in oncology-to whom does the truth belong? Oncologist 2009; 14: 77-82.

- Hamadeh GN, Adib SM. Cancer truth disclosure by Lebanese doctors. Social Science Medicine 1998; 47: 1289-94.

- Numico G, Anfossi M, Bertelli G, Russi E, Cento G, Silvestris N et al. The process of truth disclosure: an assessment of the results of information during the diagnostic phase in patients with cancer. Ann Oncol 2009; 20: 941-5.

- Oksuzoglu B, Abali H, Bakar M, Yildirim N, Zengin N. Disclosure of cancer diagnosis to patients and their relatives in Turkey: views of accompanying persons and influential factors in reaching those views. Tumori 2006; 92: 62-6.

- Shahidi J, Taghizadeh KA, Yahyazadeh SH, Khodabakhshi R, Mortazavi SH. Truth-telling to cancer patients from relatives' point of view: a multi-centre study in Iran. Austral-Asian Journal of Cancer 2007; 6: 213-7.

- Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: communication in palliative care. Palliative Medicine 2002; 16: 297-303.

- Tang ST, Liu TW, Lai MS, Liu LN, Chen CH, Koong SL. Congruence of knowledge, experiences, and preferences for disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis between terminally-ill cancer patients and their family caregivers in Taiwan. Cancer Invest 2006; 24: 360-6.

- Elger BS, Harding TW. Should cancer patients be informed about their diagnosis and prognosis? Future doctors and lawyers differ. J Med Ethics 2002; 28: 258-65.

- Grassi L, Giraldi T, Messina EG, Magnani K, Valle E, Cartei G. Physicians' attitudes to and problems with truth-telling to cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer 2000; 8: 40-5.

- Al-Amri AM. Cancer patients' desire for information: a study in a teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J 2009; 15: 19-24.

- Aljubran AH. The attitude towards disclosure of bad news to cancer patients in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 2010; 30: 141-4.

- Jawaid M, Qamar B, Masood Z, Jawaid SA. Disclosure of cancer diagnosis: Pakistani patients' perspective. MEJC 2010; 1: 89-94.

- Hattori H, Salzberg SM, Kiang WP, Fujimiya T, Tejima Y, Furuno J. The patients' right to information in Japan legal rules and doctor's opinions. Soc Sci Med 1991; 32: 1007-16.

- Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Tsilila E, Katsouda E, Vlahos L. Cancer information disclosure in different cultural contexts. Support Care Cancer 2004; 12: 147-54.

- Lee A, Wu HY. Diagnosis disclosure in cancer patients-when the family says "no!". Singapore Med J 2002; 43: 533-8.

- Oz?s?k NC, Arslan Z, Oruc OM, Sarac S, Tuzun B, Yurteri G et al. From doctors' perspective a dilemma in lung cancer; should the patients be informed about their diagnosis? Solunum 2006; 8: 102-8 (in Turkish).

- Thomsen OO, Wulff HR, Martin A, Singer PA. What do gastroenterologists in Europe tell cancer patients? Lancet 1993; 341: 473-6.

- Novack DH, Plumer R, Smith RL, Ochitill H, Morrow GR, Bennett JM. Changes in physicians' attitudes toward telling the cancer patient. JAMA 1979; 241: 897-900.

- Ferraz GJ, Castro S. Diagnosis disclosure in a Portuguese oncological centre. Palliat Med 2001; 15: 35-41.

- Ozdogan M, Samur M, Artac M, Yildiz M, Savas B, Bozcuk HS. Factors related to truth-telling practice of physicians treating patients with cancer in Turkey. J Palliat Med 2006; 9: 1114-9.

- Samur M, Senler FC, Akbulut H, Pamir A, Arican A. Cancer patient information: the results of a limited research at Ankara University Medical School Ibni Sina Hospital about perspectives of physicians and medical students. Journal of Ankara University Medical School 2000; 53: 161-6 (in Turkish).

- Faridhosseini F, Ardestani MS, Shirkhani F. Disclosure of cancer diagnosis: what Iranian patients do prefer? Ann Gen Psychiatry 2010; 9(Suppl 1): 165.

- Montazeri A, Vahdani M, Haji-Mahmoodi M, Jarvandi S, Ebrahimi M. Cancer patient education in Iran: a descriptive study. Support Care Cancer 2002; 10: 169-73.

- Tavoli A, Mohagheghi MA, Montazeri A, Roshan R, Tavoli Z, Omidvari S. Anxiety and depression in patients with gastrointestinal cancer: does knowledge of cancer diagnosis matter? BMC Gastroenterol 2007; 7: 28.

- Vahdaninia M, Montazeri A. Cancer patient education in Iran: attitudes of health professionals. Payesh 2003; 2: 259-65.

- Pulanic D, Vrazic H, Cuk M, Petrovecki M. Ethics in medicine: students' opinion on disclosure of true diagnosis. Croat Med J 2002; 43: 75-9.

- Atesci FC, Baltalarli B, Oguzhanoglu NK, Karadag F, Ozdel O, Karagoz N. Psychiatric morbidity among cancer patients and awareness of illness. Supportive Care in Cancer 2004; 12: 161-7.

- Noore I, Crowe M, Pilley I. Telling the truth about cancer: views of elderly patients and their relatives. Ir Med J 2000; 93: 104-5.

- Asai A. Should physicians tell patients the truth? West J Med 1995; 163: 36-9.

- Cassileth BR, Zupkis RV, Sutton-Smith K, March V. Information and participation preferences among cancer patients. Annals of Int Med 1980; 92: 832-6.

- Grassi L, Malacarne P, Maestri A, Ramelli E. Depression, psychosocial variables and occurrence of life events among patients with cancer. J Affect Disord 1997; 44: 21-30.

- Seo M, Tamura K, Shijo H, Morioka E, Ikegame C, Hirasako K. Telling the diagnosis to cancer patients in Japan: attitude and perception of patients, physicians and nurses. Palliat Med 2000; 14: 105-10.

- Cox A, Jenkins V, Catt S, Langridge C, Fallowfield L. Information needs and experiences: an audit of UK cancer patients. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2006; 10: 263-72.

- Jiang Y, Liu C, Li JY, Huang MJ, Yao WX, Zhang R, et al. Different attitudes of Chinese patients and their families toward truth telling of different stages of cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2007; 16: 928-36.

- Zamanzadeh V, Rahmani A, Valizadeh L, Ferguson C, Hassankhani H, Nikanfar AR, et al. The taboo of cancer: the experiences of cancer disclosure by Iranian patients, their family members and physicians. Psychooncology. 2011 Dec 2. doi: 10.1002/pon.2103. [Epub ahead of print].

- Sheu SJ, Huang SH, Tang FI, Huang SL. Ethical decision making on truth telling in terminal cancer: medical students' choices between patient autonomy and family paternalism. Med Educ 2006; 40: 590-8.

- Feldman MD, Zhang J, Cummings SR. Chinese and U.S. internists adhere to different ethical standards. J Gen Intern Med 1999; 14: 469-73.

- Tan TK, Teo FC, Wong K, Lim HL. Cancer: to tell or not to tell? Singapore Med J 1993; 34: 202-3.

- Ersoy N, Altun Y, Beser A. Tendency of nurses to undertake the role of patient advocate. Eubios J Asian Int Bioethics 1997; 7: 167-70. Available from: http://www.eubios.info/EJ76/ej76e.htm (accessed August, 2011).

- Ersoy N, Goz F. The ethical sensitivity of nurses in Turkey. Nurs Ethics 2001; 8: 299-312.

- Li JY, Liu C, Zou LQ, Huang MJ, Yu CH, You GY, et al. To tell or not to tell: attitudes of Chinese oncology nurses towards truth telling of cancer diagnosis. J Clin Nurs 2008; 17: 2463-70.

- Demirsoy N, Elcioglu O, Yildiz Z. Telling the truth: Turkish patients' and nurses' views. Nurs Sci Q 2008; 21: 75-9.

Yaz??ma Adresi (Address for Correspondence):

Dr. Sibel DORUK,

Gaziosmanpa?a ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi,

G???s Hastal?klar? Anabilim Dal?,

TOKAT - TURKEY

e-mail: sibeldoruk@yahoo.com